Where does the RBI’s surplus come from? | Explained

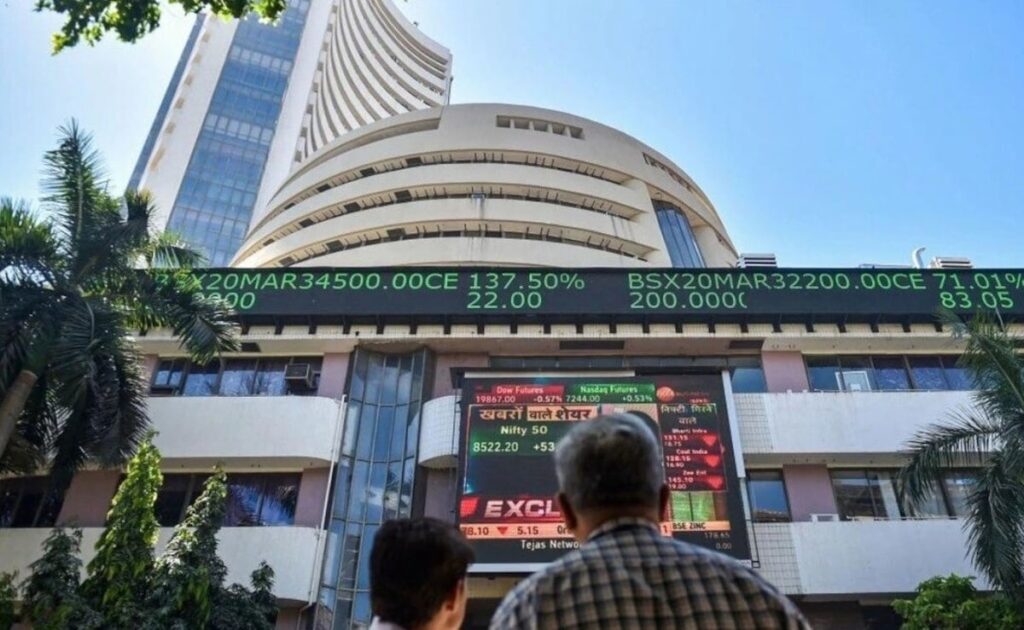

The story so far: Putting an end to much speculation, the Reserve Bank of India’s Central Board on Friday (May 23, 2025) announced that it had decided to transfer ₹2.69 lakh crore to the Central government as a surplus for the year 2024-25. This is a record high transfer, 27% higher than the ₹2.11 lakh crore transferred the previous year, which itself was a record at the time.

What had the government budgeted for?

This ₹2.69 lakh crore is also higher than what the government itself budgeted — ₹2.56 lakh crore — as dividend or surplus from the RBI, and the public sector banks and insurance companies. With the RBI’s share itself exceeding this amount, this means the government’s total collections from this category is likely to be far in excess of what it budgeted.

However, things have not always been so easy for the government when it comes to the RBI’s surplus. There have been strong arguments on both sides in the past on what should be done with the surplus the RBI earns, including some reportedly caustic remarks by Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself.

Where does the RBI get its surplus?

Before getting into the past controversy, it’s important to first understand how the RBI earns money, and also why what it transfers to the government isn’t called a ‘dividend’. The RBI is not a company in the traditional sense with shareholders, and so it cannot issue dividends.

But it is a ‘full-service’ central bank, meaning that not only does it target inflation, issue currency, and regulate the banking sector, it is also the last resort lender to the government of India and the various State governments.

The RBI can earn significant profits from some of these functions. For example, the process of issuing currency allows for the RBI to earn something called seigniorage. Seigniorage is basically the difference between the face value of a currency and the cost it took to produce that currency. When the RBI issues currency, say, a ₹500 note, the commercial banks have to ‘buy’ these notes from the central bank at the full face value (in this case, ₹500) even though it might have cost a fraction of that to actually produce that note.

This counts towards the RBI’s revenue. Then, the central bank also lends money to the Central government, State governments, and commercial banks with interest. This interest, too, adds to the RBI’s revenue. Third, the RBI makes investments in other countries’ bonds as well, not only earning interest on these, but also potentially benefiting from currency exchange rate fluctuations.

According to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, after the RBI has made provisions for bad and doubtful debt and has met all its expenses, including any provisions it needs to make towards buffer funds, “the balance of the profits shall be paid to the Central Government”.

The debate, thus, is on the size of the buffer the RBI should maintain.

What kind of buffer levels does the RBI maintain?

The main buffer fund the RBI maintains is called the Contingent Risk Buffer (CRB), which is basically a safety net in the event of a financial stability crisis.

In 2018, a committee was set up under the chairmanship of former RBI governor Bimal Jalan to determine the RBI’s Economic Capital Framework (ECF), including how big the CRB should be. At the time, the committee recommended that the CRB should be in the range of 5.5-6.5% of the RBI’s balance sheet. This was adopted by the RBI in 2019.

The Jalan committee also recommended that the ECF be reviewed every five years, which is what the RBI’s central board just completed doing. The central board decided that the CRB range would be widened to 4.5-7.5% from 2024-25 onwards.

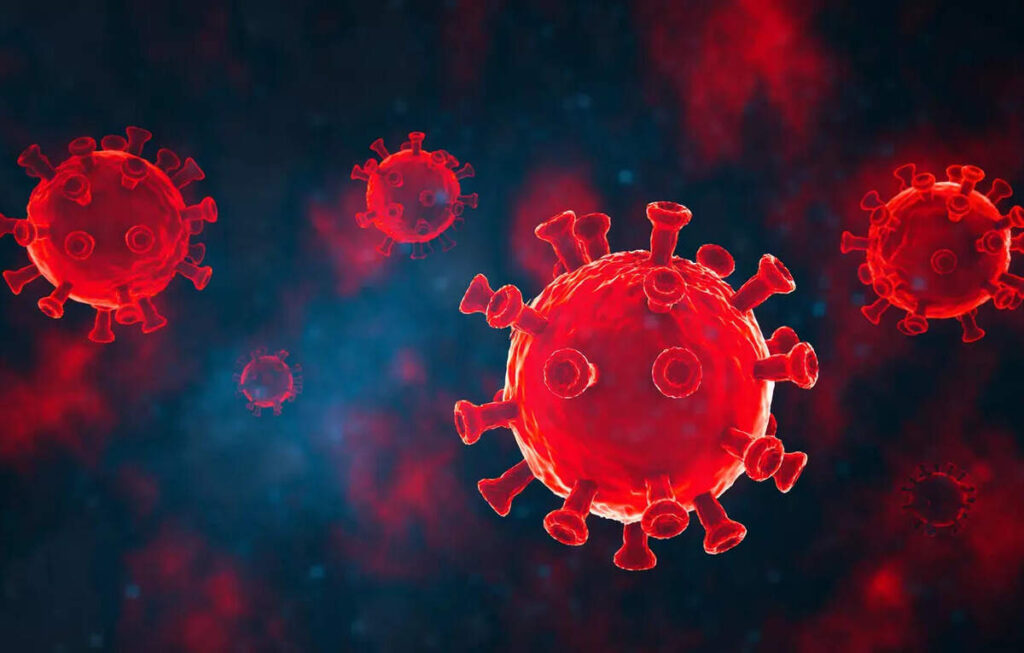

During 2018-19 to 2021-22, the RBI kept the CRB at 5.5% of its balance sheet, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy. This was then hiked to 6% in 2022-23 and 6.5% (the maximum limit at the time) in 2023-24. For 2024-25, the RBI board has decided to keep the CRB at the new highest limit of 7.5% of the central bank’s balance sheet.

The profits of the central bank have been such that — despite this higher provisioning — it could still manage to transfer a record ₹2.69 lakh crore to the Central government.

Have these transfers happened in the past without controversy?

In short, no. While the surplus transfers haven’t been the sole reason for acrimony between the RBI and the Ministry of Finance, it has certainly played a significant part.

Take, for example, the statement by then RBI Deputy Governor Viral Acharya in 2018 in which he lamented that the RBI was “neither an independent nor an autonomous institution” and that governments that do not respect the central bank’s independence will “come to rue the day they undermined an important regulatory institution”.

It was never officially clarified what this was about, but reporters covering the beat at the time knew a large part was about the government demanding large transfers of surpluses, and the RBI resisting.

Then, there’s the explosive passage in former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg’s book We Also Make Policy, in which he recounts that — during a meeting with then RBI governor Urjit Patel in September 2018 — PM Modi told Mr. Patel that he was like a “snake who sits over a hoard of money”.

Both Mr. Acharya and Mr. Patel resigned soon after their disagreements with the government. The matter subsequently died down, especially once the Jalan committee formula was adopted.

Are such large transfers the new normal?

The higher transfer this year was on account of higher foreign exchange sales by the RBI, higher earnings on its foreign exchange assets and from its liquidity management tools.

As Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at the Bank of Baroda, noted, the RBI’s foreign exchange sales — a significant driver of profits — may not be at the same level next year.

However, on the other hand, the RBI has also now provided itself a wider band for the CRB. So, if next year it decides to keep it at the lower end of 4.5%, then it could have a larger amount left over to send to the government.

Published – May 25, 2025 05:30 am IST