The people who bear the weight of a divided history

Ripples of rising hostility between India and Pakistan after the recent terror attack in Jammu and Kashmir’s Pahalgam are strikingly noticeable at Attari-Wagah, the international border between the two countries. Anguish, dismay, uncertainty, and resilience are all palpable in Punjab’s Amritsar and its border villages, even as tensions between the nuclear-armed nations and temperatures of the scorching summer continue to soar.

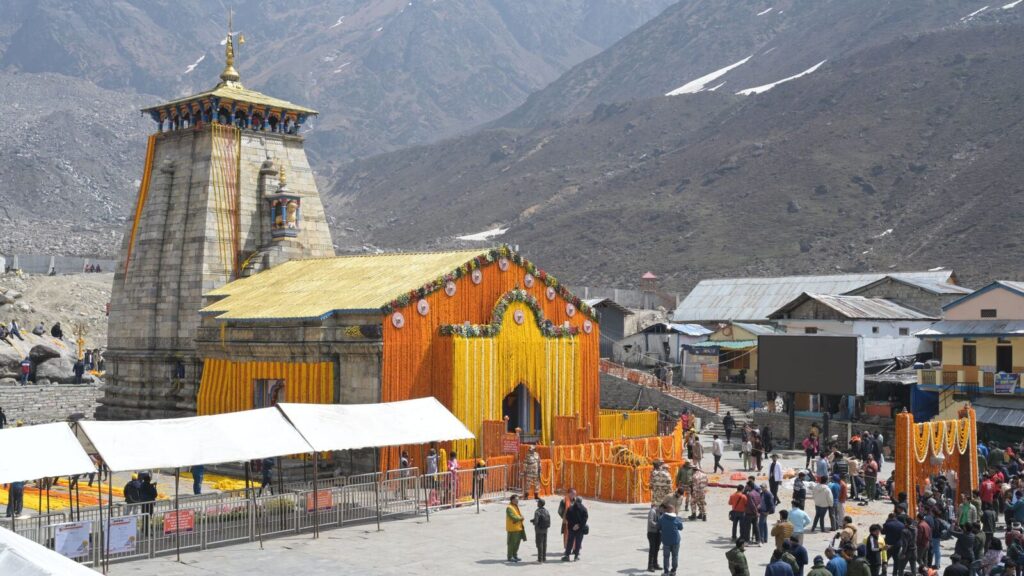

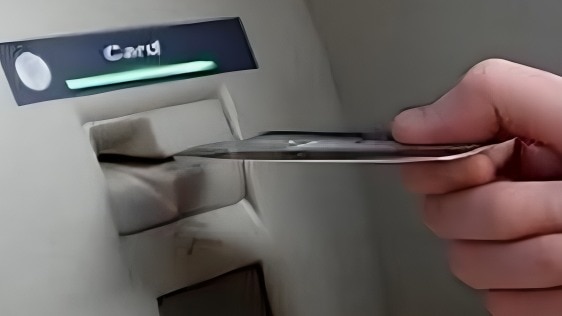

At Baisaran meadow, near Pahalgam in Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir, 26 people, all but one of whom were tourists, were killed by terrorists on April 22. A day later, India, in protest against the attack, which it attributes to Pakistan, announced a series of diplomatic measures, including the closure of the Attari border. It asked almost all Pakistani nationals to leave India. In response, Pakistan suspended trade with India and visas issued to Indian nationals. This forced several nationals from both countries to cut short their trips and return to their home country.

The deadline for Pakistani citizens on visas — excluding those on medical, diplomatic, and long-term visas — to leave India was April 27. Several people, including women and children, lined up at Attari to cross over to Pakistan. Emotions ran high with many taking unexpected and tearful leave from relatives and friends. From the Pakistani side, several Indians made their way to India. Many families with mixed nationalities are staring at separation with no end date.

“My wife Savita has a Pakistani passport, but my two kids are Indian. They had gone to Pakistan to meet her family a few days ago. We have been married for 13 years and she has visited Pakistan on different occasions and returned. This time she is being held back. The authorities in Pakistan are allowing only our children to return,” says Rishi Kumar from Maharashtra’s Kolhapur. He reached Attari on April 24 and stood waiting outside the Integrated Check Post (ICP).

“Why are we being separated? I don’t know what to do now. What happened in Pahalgam is condemnable beyond words, but I hope and pray the situation doesn’t deteriorate between the two countries. Peace should prevail,” says Kumar, who spent three days trying to find a way to reunite with his family. After five days of turmoil, on April 29, he heaved a sigh of relief when Pakistani authorities allowed his wife and children to cross over to India.

Families fret

As many as 537 Pakistani citizens left India between April 24 and 27, when the first deadline came to an end, while 850 Indians arrived from Pakistan. On April 28 and 29, as many as 249 Pakistanis left India via the ICP, while 527 Indians returned to the country

.Over the years, families and communities that were split at the time of Partition have attempted to stay in touch via the trans-boundary connect. But whenever bilateral relations are strained, people suffer. Despite the creation of India and Pakistan as separate countries in 1947 — a time that was marred by violence and bloodshed — a sense of shared cultural identity across the border has remained intact for years.

Attari-Wagah has stood witness to both turbulent times and kinship. Being the only land route for trade and travel between India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, its economic significance has been critical over the years, especially for locals. It is situated on the historic Grand Trunk Road, one of South Asia’s oldest, which dates back to the Mauryan period, though it was redone by Sher Shah Suri, one of the rulers of Delhi.

Organised since 1959, the Beating Retreat ceremony at the ICP every evening is a key attraction for tourists from across India. Both countries lower their flags, with the Border Security Force (BSF) and the Pakistan Rangers playing key roles. The tone of the ceremony, whether amplified or moderated, indicates the depth of strained ties and the level of animosity. Now, it is low-key, with half the attendance compared with the usual turnout of 25,000 on weekends and 18,000-20,000 on weekdays, a BSF officer says.

Vehicles with Pakistani nationals crossing the border.

| Photo Credit:

SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

With a short window to exit India, people jostled at the ICP to cross over to Pakistan, even as they made their way in vehicles and autorickshaws loaded with luggage to the passenger terminal guarded by the BSF. While those holding a Pakistani passport were allowed to leave, the others, even family members, were stopped.

An upset Wajeeda Khan, 24, an Indian national who married a Pakistani and came to India in February to meet her parents, is uncertain about reuniting with her husband, who is waiting on the other side of the border. “I am an Indian and got married a decade ago in Karachi. My two children were born in Pakistan and they are Pakistani nationals. How can I stay here and send my children across the border?” she says, tearfully.

Elham Destani, an Iranian national and solo traveller, is worried about reaching her country. “I travel across the globe in my camper van to spread the message of peace. Attari-Wagah is the only road route for me to reach my home in Iran. I have a ‘tourist visa on road’ and I have been in India for the past 75 days. I just want to go back home,” she says, dejected as she parks her van on the roadside close to the ICP.

The Attari-Wagah border is both a physical and symbolic gateway. In 1999, then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee started the Delhi-Lahore bus service through this border and travelled on the inaugural bus to meet then Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

Blood and country

Many Indian nationals arriving from Pakistan expressed anguish over the Pahalgam terror attack, justifying India’s firm stance.

Ali Hasan, 58, says, “I am an Indian first. We have blood ties across the border, but that is secondary for us. What happened in Pahalgam was inhumane and I stand with my country.”

His uncle’s family went to Pakistan at the time of Partition and chose to settle in Lahore, about 50 km from Amritsar, once twin cities. “My cousin was unwell, so my wife and I went on April 8 on a month-long visa to meet him,” says Hasan, who is a farm worker in Haryana’s Sonipat.

Travellers producing their passports at the Integrated Check Post.

| Photo Credit:

SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

After the terror attack, the BSF scaled down the Beating Retreat ceremony at three locations — Attari, Hussainiwala, and Sadki — along the Pakistan border in Punjab. Among the three posts, Attari witnesses the maximum crowd.

On April 26, as the sun went down, the border gates remained closed during the ceremony at Attari and the symbolic handshake between the Indian guard commander and the Pakistani counterpart didn’t take place. These steps, according to the BSF, reflects “India’s serious concern over cross-border hostilities and reaffirms that peace and provocation cannot coexist”.

Usually, patriotic songs are played during the soldiers’ perfectly rehearsed drill. People from the spectator gallery join the chorus in nationalistic fervour, waving the flag, with the Tricolour painted on their faces. The festivity, including dancing by visitors, is dull though.

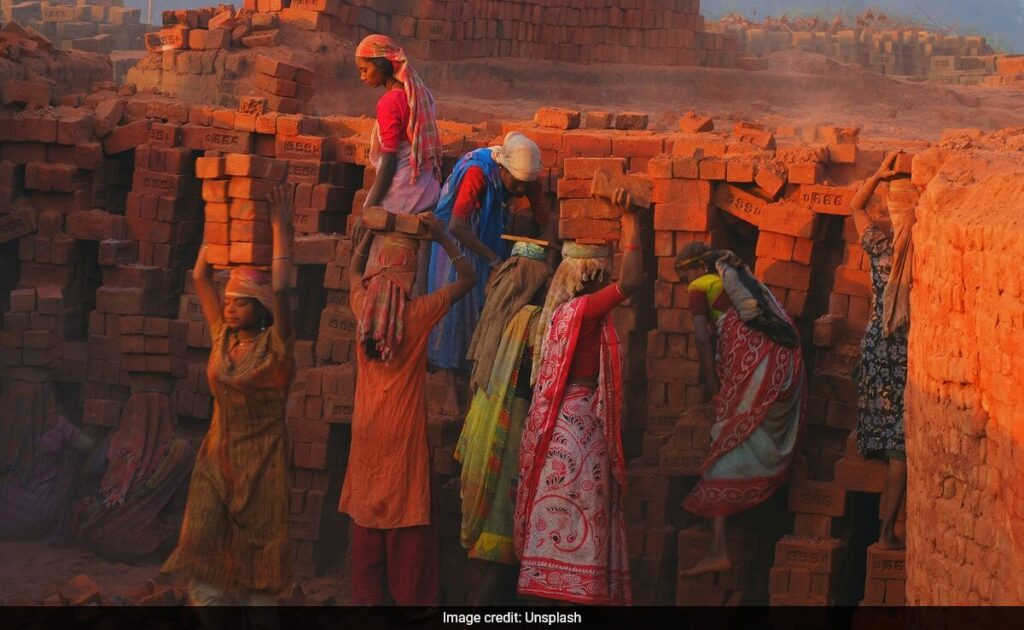

“We are the immediate sufferers whenever tensions escalate between India and Pakistan. There are hardly any customers in dhabas now and daily business has taken a hit. Once the check post is completely shut down, our future will be bleak. We stand with the country but request the government to ensure that some steps are taken for our survival as well,” says Abhijit Singh, who runs a dhaba opposite the ICP.

At Attari, while locals stand firmly by the decisions of the government, they are concerned about their livelihood in the absence of cross-border trade. Local businesses have already taken a hit since the halting of bilateral trade following the Pulwama terror attack in 2019. Since then, there has been only sparse cargo movement from Afghanistan at Attari’s land port at the ICP. However, this too has been stopped for now, impacting traders, customs house agents, truckers, and porters, among others.

Tarsem Singh, a 38-year-old porter, says, “Once the ICP completely shuts down, life will be difficult for me and many others like me. Already, the trucks that were coming from Afghanistan have stopped, so there has been no work at the cargo terminal since April 24. The passenger terminal will be closed in a few days. Where will I go? How will I sustain my family?” he says, dropping his head in despair.

Away from Attari, at Dera Baba Nanak town in Gurdaspur district, the Kartarpur Corridor, which connects Kartarpur Sahib gurdwara in Pakistan with Dera Baba Nanak shrine in India, is still open and pilgrims continue to access the historic gurdwara in Pakistan without the need for visas. Notably, amid the ongoing tensions, Pakistan has suspended visas of all Indians except Sikh pilgrims. Pilgrims from India continue to travel to Kartarpur to pay obeisance at the gurdwara and return the same evening.

A matter of safety

Punjab villages adjacent to the international border have often been at the receiving end of diplomatic fallout and economic disruptions. About80 km from Attari, in Gurdaspur district’s Rose village, situated on the international border, the sentiments are somewhat different.

“There’s no sense of fear among the villagers. It’s not the first time that there has been tension with Pakistan; we are used to it and not afraid. In 2016, when India conducted surgical strikes, villagers were asked to move to a safer place, but hardly anyone left the village. We don’t run. In fact, if the situation demands it, we will help the Army in whatever way we can,” says 58-year-old Harkeet Singh, who is harvesting wheat on his 100-acre farm situated close to the fence constructed by India near the ‘zero line’, the actual boundary line between the two countries.

He says it is difficult to cultivate here as there’s limited time given for farm operations. “Each time I go to my farm, I have to take permission and complete paperwork. It’s time-consuming. On the Pakistani side, there’s no fencing, so the stray cattle damage the crop. Problems are there and we want the government to solve our issues. But now, our nation’s priority is our priority.”

Even as tensions continue to escalate between the two neighbours, the scars of a violent past and the pain of families torn apart resurface. “I hope the situation normalises soon. Whenever tension rises between India and Pakistan, residents of the border villages have to bear the brunt,” says Daljeet Singh, 60, who is in a hurry to harvest the wheat crop on his 1.5-acre farmland close to the international border.

vikas.vasudeva@thehindu.co.in

Edited by Sunalini Mathew

Published – May 01, 2025 11:58 pm IST